Where we work

Research is conducted in Namibia, in the Erongo Mountains and the Spitzkoppe area, and in South Africa, around Kimberley

To test the Cosmopolitan Approach, two areas have been selected for case studies and are at the heart of the implementation of the COSMO-ART project: rock art sites located in the≠Gaingu Conservancy (Erongo, Namibia), in the Erongo Mountains and the Spitzkoppe Massif, and in the Kimberley area (Northern Cape, South Africa).

In the ≠Gaingu Conservancy, the sites were selected because:

Existing contacts (HNHP) and the involvement of Namibian researchers working in the area (Martha Akawa, Kaarina Efraim, Emma Haitengi & Alma Nankela), provide excellent conditions for fieldwork there.

Erongo

The Erongo Mountains (historically called ǃOeǂgabKlicklaut in Khoekhoegowab) are a mountain range of volcanic-plutonic origin in Namibia. It is located in Damaraland, southwest of the town of Omaruru, south of the river of the same name and east of the Damara communal area. It gave its name to the Erongo Region, one of Namibia's administrative divisions.

The Erongo Mountains contain thousands of rock paintings (and some engravings), most of which are estimated to be over 2000 years old. In 1998, a number of landowners met to establish a trans-boundary private nature reserve. This idea was initiated and is still supported by hunters who use their land for the sustainable exploitation of naturally occurring game. Most of the twenty large farms in these mountains are now grouped in the Erongo Mountain Nature Sanctuary. This reserve aims to protect the indigenous flora and fauna of the area and to reintroduce species that were historically part of the natural biodiversity. The creation of this reserve has resulted in the unprecedented removal of almost all internal fencing and individual boundary fences to allow wildlife to roam freely. A large area - almost 180 000 hectares - is now almost completely fenceless and therefore fully available for the protection and conservation of the animal and plant species that occur there. Within these 180,000 hectares, game can roam freely. The only fencing is at the borders of the sanctuary, where there are no mountains, to prevent the reintroduced black rhino from straying into neighbouring farmland.

The Erongo Mountains have become a popular tourist destination in recent years. While previous generations of landowners made their living from cattle ranching, most now work in the tourism industry. This can be nature tourism, rock art tourism or hunting tourism.

Spitzkoppe

Spitzkoppe (locally known as ≠Gaingu, meaning "the last great mountains on the way north") rises 700 m above the surrounding plains. It lies about 100 km from the Atlantic coast and is surrounded by an arid, endless plain. It consists of two large hills: the large dome of the Gross Spitzkoppe and the multi-domed Pondok Mountains. The Gross Spitzkoppe (or "Big Spitzkoppe"), also known as the "Matterhorn of Namibia", rises to an altitude of about 1728 m. The Pondok Mountains are named after the local dome-shaped huts made of bent branches and smeared with cow dung. A wide gap separates the Gross Spitzkoppe from this series of granite hills. A third mountain range, the Klein Spitzkoppe (or "Little Spitzkoppe"), lies 15 km to the west and rises to 1584 m above sea level. Gross and Kleine Spitzkoppe are inselbergs, defined as prominent steep hills of solid rock that rise abruptly from a plain of low relief.

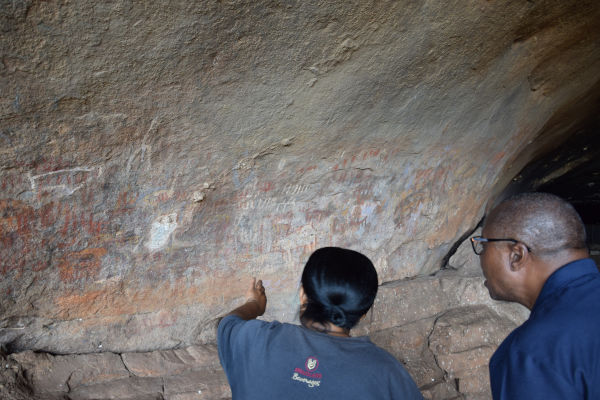

Archaeological remains (including at least 37 rock art sites) indicate a pattern of settlement and subsistence sites attributed to hunter-gatherers who lived in the area at least until the introduction of domesticated animals in the last millennium. Rock art is found at the foot of the hills, between large boulders on several sheltered rock faces and under overhanging walls similar to those at Bushman's Paradise (the best known and visited rock art site in the area). Although the exact age of the rock art is unknown, it is thought to date from the Ceramic Later Stone Age, when nomadic pastoralism became the dominant economic activity. The remains of a short-lived German colonial outpost from the end of the last century can also be seen at the foot of the Pondok Mountains.

Although the area attracts a large number of tourists (it has been known for its scenery and climbing spots for decades), unemployment is widespread in the village of Spitzkoppe (about 1200 people). With limited income-generating opportunities, hundreds of people struggle to find food on a daily basis. Income is generated by small-scale livestock farming, the informal sector and tourism. Spitzkoppe has a limited amount of land suitable for agriculture due to lack of water. As a result, the existing land suitable for livestock grazing has been overgrazed. The area is rich in biodiversity with unique plant, bird and animal species found only in these unique geological areas. At the same time, it is a very fragile environment under pressure from the number of visitors to the area and the use of natural resources.

The sites selected in the Kimberley region are all National or Provincial Heritage Sites and are open to the public.

The focus is on Wildebeest Kuil, where tourism development (since 2000) has involved local communities. The "local" communities here are people who were displaced at the end of apartheid and are related to San cultural groups from northern Namibia and southern Angola. They are involved in reformulating why and for whom rock art sites are heritage in a socio-economic context characterised by very high unemployment rates and a history of mining.

Two other nearby sites with engravings (Driekopseiland and Nooitgedacht) have also been selected to provide points of comparison, with slightly different conditions (landscape, local community, ownership and mode of tourist development).

A fourth site, Wonderwerk Cave, is further north, between Daniëlskuil and Kuruman, and is very different. It is a painting site in a deep dolomite cave and is best known as an archaeological site that has been excavated since the 1940s. It was chosen because of an interesting combination of features (paintings, archaeological sites, accessible only with a guide, extensive tourist infrastructure and development still in progress, presence of a local community with a strong relationship to the cave but experiencing difficulties in accessing it) that are directly related to the aims of COSMO-ART.

The involvement in the project of members who have long studied the sites and are responsible for their management (Abenicia Henderson & David Morris) and who teach at the Department of Heritage Studies at Sol Plaatje University (Lourenço Pinto & Gilbert Pwiti) provides excellent conditions for the realisation of the project.

Driekopseiland

Driekopseiland is a site where engravings are found on a glacial pavement (rock smoothed by the action of glaciers) exposed on the banks of the Riet River, about 70 km from Kimberley. The site is densely populated with images. It contains more than 3,500 individual engravings, mainly pecked geometric images. The images are submerged when the rains come during the wet season, but are also left dry when the flow of the river decreases.It is estimated that the engravings were made in two episodes – before about 2500 years ago and after about 1000 years ago, based on archaeological and geomorphological considerations.

Debates over the authorship of the rock art at the site have been particularly heated. For some researchers, the overwhelming preponderance of geometric engravings, with very few animals and virtually no human figures, links the site to the rock art tradition of the Khoekhoe herders. Another approach, while not ruling out the hypothesis that different identity groups were responsible for some of the variability between sites, asks whether attributing variability to ethnic or cultural differences overlooks degrees of complexity. It is suggested that a metaphorical understanding of place - and the possibility that different parts of the landscape may vary in ritual terms - may be more relevant to questions of variability in the rock art of the region than arguments based primarily on ethnicity and cultural difference.

Driekopseiland was declared a National Monument in 1944. It automatically became a Grade 2 Provincial Heritage Site when the National Heritage Resources were proclaimed in 1999.

A weir was built across the upper part of the site in 1942, permanently submerging an estimated 150 engravings above the weir and altering flood dynamics and siltation patterns. The latter, in turn, led to increased reed growth and an invasion of eucalyptus saplings into silted parts of the site - aided by increased flow following the construction of a canal from the Orange River to the Kalfontein Dam (on the Riet River) in 1987.

Nooitgedacht

The engravings at Nooitgedacht are found on a glacial andesite pavement (rock smoothed by the action of glaciers) from the Dwyka (or Karroo) Ice Age, some 300 million years ago, and more recently exposed by erosion.

The engravings are mainly animal outlines and geometric designs made by pecking out the outer, darker surface of the rock. They are attributed to the ancestors of the San and Khoe peoples and were probably made within the last 1,500 years. The engravings include depictions of humans, eland, rhino, ostrich, giraffe and anteater. More abstract forms may represent bags and aprons, as well as 'geometric' images such as those found at other sites in the region, notably Driekopseiland.

The site was declared a National Monument in 1936 and is now a Grade 2 Provincial Heritage Site. It is open to visitors on self-guided tours.

Nooitgedacht Farm was also the site of diggings for high-grade alluvial diamond in the second half of the 20th century.

Wildebeest Kuil

Wildebeest Kuil is a rock art site located about 16 km from Kimberley on an andesitic koppie (hill). The site has long attracted the attention of rock art researchers and enthusiasts, with the earliest known copies made by George William Stow in the 1870s. Some of Stow's engravings were removed in the late 19th century and exhibited at the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London, and at least two are now in the British Museum. When G. and D. Fock documented the Gnu Kuil in 1968, they recorded 178 engravings. Since then, in-depth studies have revealed a much larger number of engravings and man-made markings.

Most of the engravings were made by pecking out the surface of the darker rock to expose the lighter rock underneath. They mainly depict large animals such as eland, elephant, rhino and hippo. Stone circles and clearings on and around the hill were already mentioned by Stow in the 1870s. One of these was excavated by Peter Beaumont in 1983 and revealed levels of Later Stone Age occupation dating from between 1800 and 1200 years ago. It is possible that the engravings were made by the occupants of the site during this period.

More recently, the site was occupied by the Khoe-San leader Kousop and his family. Kousop is famous for leading the resistance to colonial expansion in the area and was killed in 1858. A hotel was also built on the site and operated between the 1870s and the early 20th century.

Today the land belongs to the !Xun and Khwe San people of nearby Platfontein, and a rock art centre has been operating there since 2001. The site has been declared a Provincial Heritage Site and is managed by the Northern Cape Rock Art Trust in association with the McGregor Museum

Wonderwerk

Wonderwerk Cave is about 200 km north-west of Kimberley. The cave is a large tunnel-like cavity measuring 140 m long, 10 to 25 m wide and 3 to 7 m high above modern ground.

There is rock art on both walls, in the partially lit entrance area. It consists of painted figures, mainly finger-painted geometries in black, white, red, orange and yellow. There are also animal figures of varying degrees of realism. No artefacts have been found below the surface of the floor during the various excavations, which suggests that it is relatively recent, or at least cannot be dated using archaeological levels.

The cave has yielded a wealth of archaeological remains. The oldest remains date back to the Early Stone Age, with 2-million-year-old levels in the entrance area attributed to the Oldowan. They raise the question of the early use of fire, as they contain burnt bones while no fire structures are visible. A series of Acheulean levels in the entrance area are characterised by the presence of handaxes and well-preserved plant and animal remains. In the cave, the Early Stone Age ends with the Fauresmith. This complex can be found at the bottom of the cave and has been dated to between 780,000 and 187,000 years ago. It has been suggested that the remains show traces of symbolic behaviour with the collection of non-utilitarian crystals, pebbles and incised stone slabs. Early Middle Stone Age levels are found at the end of the entrance. Ochre is present in these levels, but there are no traces of the symbolic behaviour typical of this period. Finally, the Later Stone Age levels in the entrance area have been extensively excavated. This occupation lasted from 12,900 to 900 years ago. It yielded 5 engraved stone slabs depicting animals and geometry, which at the time of their discovery were the oldest pieces of art mobilier in southern Africa. Pigments are present in all the Later Stone Age levels. Two stone slabs are interpreted as palettes.

In the 19th century, one of the main roads leading to the Moffat Mission in Kuruman passed right by the cave. This mission was one of the main stops for travellers heading north when the country was being colonised. At that time, the Kuruman hills were still inhabited by hunter-gatherers, and the cave was reportedly used to hide stolen livestock and to collect water. The paintings are also briefly mentioned, but without any comment on their condition. In 1906, however, a report to the Cape Town Legislative Assembly stated that the paintings had “nearly all been destroyed, visitors having scribbled over and otherwise defaced them.”

Between 1909 and 1911, the cave was occupied by the Bosman family while they built their farmhouse. They then used the cave to store farm equipment and house livestock until the 1930s. In 1921 Maria Willman, then director of the McGregor Museum in Kimberley, made three watercolour copies of some of the paintings in the cave. In the early 1940s, the Bosman family carried out extensive work in the cave to remove the guano-rich sediments and sell them as fertiliser. This work had a destructive effect on the upper archaeological levels, but led to the discovery of archaeological remains and attracted the attention of archaeologists, who quickly began excavations that continue to this day. In the 1960s, J. and I. Rudner and G. and D. Fock reported on the cave paintings in their surveys of rock art in the region. Throughout the 20th century the cave was visited by people from nearby towns and farms. They often wrote their names and dates on the walls, often above the rock art. Recreational use of the cave slowed in the 1970s when a fence was erected to control access to the cave. In 1993, the cave and surrounding public easement were declared a National Monument (reclassified as a Grade 1 National Heritage Site in 2010) and work was undertaken to regulate public access to the cave. Accommodation and a small exhibition area have been built. Inside the cave, a path has been laid out to restrict and make safe the route taken by visitors. Restoration work was carried out by the artist Steven Bassett to remove the graffiti that had covered the paintings. Since then, the cave has been managed by the Wonderwerk Cave Committee, which consists of the McGregor Museum, the owner of the surrounding farm and a representative of the Kuruman Municipality. A management plan was drawn up in 2008 in preparation for upgrading the cave's status in 2010. The cave continues to be a spiritual place for the local communities. People come here to perform rituals related to syncretic religious beliefs.